When you're taking photos, it's important to keep in mind that your camera may not always focus on the exact spot that you want it to. This is called focus shift, and it can be a real problem when you're trying to take a good photo. In this article, we'll discuss what causes focus shift and how to deal with it when you're taking pictures.

What Are the Symptoms of Focus Shift?

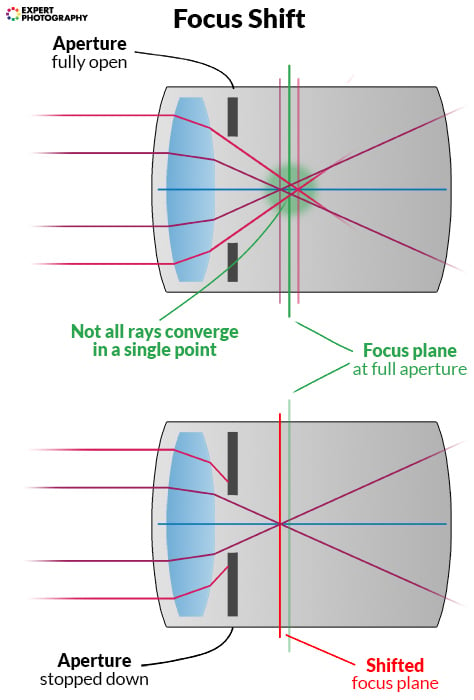

You can recognise the focus shift by the symptoms depicted above. If your lens is calibrated, and performs well wide open, but not slightly stopped down, it has focus shift.

I almost always notice focus shift when shooting portraits. I’m focusing on the eye, but the focus moves to the eyelashes sometimes due to focus shift.

You can’t bypass focus shift by switching to manual focus. You can only get rid of focus shift if you use the same aperture to focus and shoot. Most cameras don’t work like that.

It’s mainly an issue with prime lenses that have a maximum aperture wider than f/2. Macro-capable lenses are usually corrected against it. They need to work correctly at a very shallow depth of field.

Video-oriented lenses often show a noticeable focus shift when used in photography. In video work, you focus at the same aperture where you shoot. So, it’s not an issue in a video, and manufacturers prioritise other factors when designing video lenses.

It’s also not price-dependent: the Canon EF 50mm f/1.2 has focus shift, while the Sigma 50mm f/1.4 Art does not.

Don’t Confuse Focus Shift With Misalignment

A more noticeable, similar problem is focus misalignment in DSLRs. This problem occurs when the lens and the camera are not calibrated together.

The critical difference is that misalignment affects the focus plane at all apertures. Focus shift, on the other hand, only messes up things at wide aperture, but not the widest.

Misalignment is easy to correct in most cameras. Canon, for example, has AF Micriadjustment built-in. Sigma offers a USB dock that allows you to finetune your individual Sigma lens copy.

You can’t do this with focus shift. Solutions exist, but they are either too meticulous or don’t involve camera settings at all.

Why Focus Shift Exists

Focus shift is a consequence of uncorrected spherical aberration.

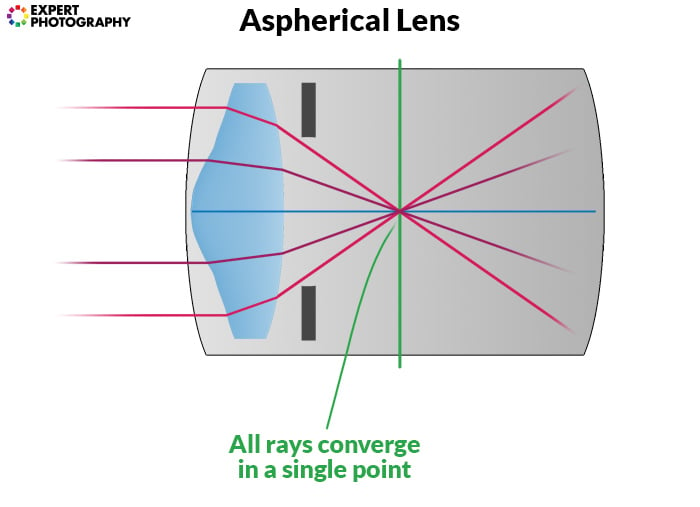

In an ideal lens, light rays from the focus plane converge in a single point. That would result in a clean, sharp image of everything in focus.

But lenses are never ideal. Spherical aberration affects them all, to a varying degree.

You can correct spherical aberration to an unobtrusive level. This correction can be achieved using aspherical elements and advanced coatings.

But these have always been expensive. So expensive, that even Canon’s flagship 50mm doesn’t have aspherical elements. (They’re starting to make their way into consumer lenses. So, we can expect a significant improvement in the future).

Without aspherical elements, light rays don’t converge in that single point. Instead, especially at the widest aperture, they are slightly scattered. This scatter results in a blurrier image than stopped-down aperture.

But of more importance here, it also results in a different sharpest focus plane. Compared to stopped-down aperture, it is further behind.

There’s a big problem with this.

In photography, we focus the lens at its maximum aperture. There are many reasons for it:

- More light. In a brighter viewfinder, we see the image better, which helps manual focusing. In live view, the image is less noisy. The autofocusing system is more accurate in bright light, too.

- PDAF works exponentially better. Phase detection autofocus systems struggle at narrow apertures because phase differences are smaller.

- Shallower depth of field. We can clearly see the area of focus when it’s shallow. At narrow apertures, we’d have to guess more to find the correct focus.

However, we often stop down the aperture to achieve a sharper image.

The actual closure of the iris only happens when we press the shutter button.

In this situation, we focus at a wider aperture than at what we shoot. And if that wide aperture has a different focal plane than the one we shoot at – well, our focus will shift.

As I mentioned above, aspherical elements are the most efficient at correcting this. In such lenses, the light coming from in-focus objects will converge in a single point. (Or, at least, an almost point-like area).

How Can You Avoid Focus Shift?

There are options to avoid focus shift. I don’t like most of them, but they are useful to know.

Avoid the Affected Apertures

The problem only affects a few aperture steps. It doesn’t affect wide-open apertures.

But it also leaves apertures above ~f/2 in peace. At those settings, the depth of field is large enough to cover both the shifted and the original focus planes.

So, you might choose to not shoot at the problematic apertures.

Focus While Stopped Down

Focusing, while stopped down, has severe limitations.

For this, you’d have to focus manually, while holding the DoF preview button. You can’t use autofocus. Not because of physical limits – it’s blocked.

In many cameras, there’s no other option for stopping down other than holding the DoF button. To stop down and lock the aperture, you’d have to press the button and twist the lens to stop electronic contact.

This applies to everything from Canon. I don’t have a broad experience with other brands, but I suspect most cameras have this limitation.

The Panasonic GH5 (and most other Panasonic cameras, too) has the option to lock the aperture in a stopped-down position. This was a pleasant surprise for me. The option is called ‘Constant Preview’, and it’s available in manual mode.

Get to Know Your Lens

The best solution is to learn the behaviour of your lenses and focus according to this.

This process is long, but useful because you can maintain the speed of operation.

Once you get familiar with rates by which your lens shifts at certain apertures and subject distances, you can compensate.

This looks something like this on the 50mm f/1.2 lens:

I have a subject at a 1-metre distance from the camera. I set my aperture to f/1.8, for increased sharpness.

I’ve come to know that in this setup, I need to focus half an inch behind where I want my real focus.

You can do the same thing for your gear.

Photo by Aris Ioakimidis from Pexels

Conclusion

Focus shift is not an issue that can have a drastic effect on your photographs, but it’s a thing to be aware of.

It can be very annoying when you buy a lens for a four-digit sum, and it misses focus at f/1.6.

If the reason is not miscalibration, it’s focus shift, and now you know how to counteract it.

Why not check out our articles on spherical aberration, focus stacking or using manual focus next!