As a photographer, you have a vast selection of lenses to consider. Those that show a vast portion of a scene are called wide-angle lenses.

But do you need one? Also, which wide-angle is the best camera lens choice for you? To answer these questions, let’s examine the types of wide-angle lenses available and when to use them.

Our Top 3 Choices for the Best Wide-Angle Prime Lens

What Is a Wide Angle Lens?

First, we must clarify the meaning of “wide angle.” The most common description is that a wide-angle lens displays a wider field of view than our vision. But this doesn’t translate directly to millimeters (mm) and degrees.

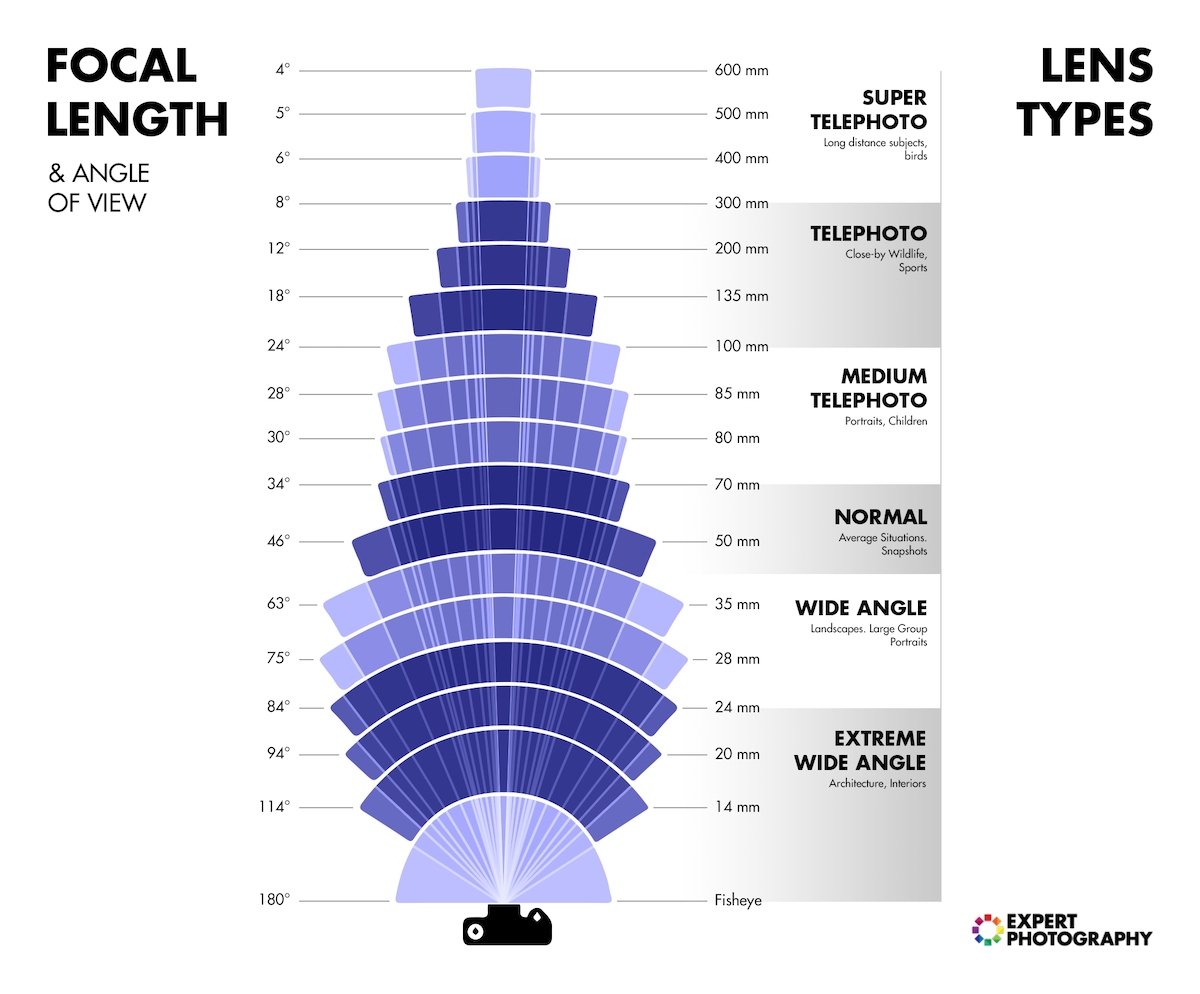

So, what focal lengths (in mm) can be considered wide-angle lenses? The popular definition is that a lens below or equivalent to 35mm is considered a wide-angle lens. This is roughly 63 degrees of a diagonal field of view.

Does a Wide-Angle Lens Zoom?

All lenses, including wide-angle lenses, are available in either a prime or a zoom version. A prime lens has a fixed focal length, meaning you can change your field of view by moving closer or further away.

Primes are generally lighter, faster, cheaper, and produce better image quality. The Canon 24mm f/2.8 STM is a great example of a small and cheap prime lens.

A zoom lens has a variable focal length (zoom range). Some all-around zoom travel lens options cover wide, standard, and telephoto focal lengths. Most zoom lenses are more specific, giving you one or two of these.

Zoom lenses are versatile, letting you keep your gear to a minimum. But a zoom lens is generally heavier and more expensive due to extra mechanisms and glass inside the lens. Kit lenses are exceptions. They are often quite small, but they come with serious compromises.

Prime lenses usually surpass a zoom lens’s image quality in the same price range. A zoom lens is a jack of all trades, a master of none.

The Canon EF 16-35mm f/2.8 III lens is an excellent example of a professional wide-angle zoom lens. The mirrorless equivalent would be the Canon RF 15-35mm f/2.8L USM.

How Wide Is a Wide-Angle Lens?

As I mentioned, a wide angle means anything below 35mm (by popular definition). But there’s still a lot of room for further specifications.

Focal lengths between 35mm and 24mm are considered standard wide angles. We usually refer to the wide angle between 24mm and 16mm. Focal lengths below 16mm are considered ultra-wide angles.

The most popular wide-angle zoom range is 16-35mm. Most kit or standard zoom lenses are 24mm or 28mm. The widest lenses on the market are 10mm (rectilinear lenses) and 8mm (fish-eye lenses).

But we have to make a disclaimer here. The camera that you use influences how your lens’s view will “look.” Smaller camera sensors crop out the center portion of any lens. This results in a tighter field of view.

For simplicity, all focal lengths mentioned here are full-frame camera equivalents. To discover how these translate to your camera, divide them by 1.5 for APS-C cameras or two for Micro Four Thirds cameras.

What Are the Three Main Types of Wide-Angle Lenses?

We differentiate between three main sorts of wide-angle lenses in terms of distortion.

1. Fish-Eye Wide-Angle Lens

Fish-eye lenses are special ultra-wide-angle lenses. Their angle of view is usually 180 degrees, letting you see half of a full rotation. They are at the bottom of the scale in terms of focal length.

They have a distinctive, hemispherical type of lens distortion. They cram in as much information as possible. Thus, they don’t produce straight lines. Like the GoPro, most action cameras also feature built-in wide fish-eye lenses.

The Rokinon 8mm f/3.5 HD is a great example. There are a few fish-eye zoom lenses, like the Canon EF 8-15mm. And there’s an ultra-rare 6mm f/2.8 fish-eye made by Nikon.

Shot with an Olympus OM-D E-M10 Mark II and a fish-eye lens. 8mm, f/5.6, 1/180 s, ISO 100. Photo by Peyne François (Unsplash)

2. Rectilinear Wide-Angle Lens

Rectilinear wide-angle lenses are the other type. Any wide-angle lens that’s not explicitly marked as fisheye is rectilinear. These are not free from distortion either. But they keep lines close to straight.

You might still notice moderate barrel distortion on some. It is more obvious in architectural images, where the lines bow outward, away from the center. But it’s also easy to correct during post-processing.

Although some are close, they won’t give you a full 180-degree field of view. Some of the widest lenses available are the Rokinon 10mm f/2.8 ED, the Samyang XP 10mm f/3.5, and the Voigtlander 10mm f/5.6.

Remember that you cannot compare a 16mm fisheye with a 16mm rectilinear wide-angle lens. Because of the distortion, the fisheye lens will give a different, slightly wider image.

The Canon EF 28mm f/1.8 USM is an all-around rectilinear wide-angle lens for Canon DSRL. I strongly recommend the Canon 24mm f/1.4L II lens if you have the budget. It’s one of my all-time favorites.

There are also Canon mirrorless camera equivalents. There is the RF 28mm f/2.8 STM and the RF 24mm f/1.8 STM.

Lines straightened. Shot with a Nikon Z6 II at an ultra-wide angle. 14mm, f/6, 1 second, ISO 125. Photo by Peter Herrmann (Unsplash)

3. Tilt-Shift Wide-Angle Lens

Although tilt-shift lenses don’t necessarily have to be wide-angle lenses, most are. Neither of the previously mentioned two lens types lets you correct for perspective distortion.

This type of distortion is especially prevalent in wide-angle lenses. You’re not viewing two parallel lines directly from the middle. With a standard rectilinear lens, they would converge. And tilt-shift lenses take rectilinear a step further.

Tilt-shift lenses project much larger images than the full-frame sensor. You can move the lens horizontally and vertically on the plane parallel to the sensor.

Thus, they can make converging lines parallel or parallel lines converge. And you also have the option to independently control (tilt) the plane of focus.

These lenses are extremely sophisticated and very expensive. They are the most popular lenses among professional architectural and fine-art photographers.

My favorite is the Canon TS-E 24mm f/4L UD. It’s a very versatile lens. You can even attach a teleconverter to make it a longer tilt-shift lens.

Shot with a Panasonic DMC-TZ61 and its tilt-shift function. 17.5mm, f/5, 1/320 s, ISO 100. Photo by Xavier Foucrier (Unsplash)

6 Best Ways to Use a Wide-Angle Lens

So, what is a wide-angle lens used for? Wide-angle lenses are generally used for scenes you want to capture as much as possible. Landscapes, cityscapes, and architecture are the main categories that use a wide-angle lens.

A fish-eye lens captures even more of the scene but is mainly used for artistic and creative purposes. They are wide enough to nicely capture the two-worlds scene most of us have seen and admired.

You must be conscious of your composition to work well with a wide-angle lens. It is easy to fall into the trap of showing too much.

1. Street Photography

I often use my wide-angle lens for street photography. If I need to get closer to a subject, I move there myself.

As Robert Capa taught us, “If your images aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” With wide-angle lenses, this can be a pain, as you need to get very close. But it can also give a dramatic perspective and a sense of presence.

I recommend a fast 35mm or 24mm prime lens for street photography, especially in challenging lighting conditions.

Shot with a Leica TL2. 18mm, f/6, 1/125 s, ISO 125. Photo by Peter Herrmann (Unsplash)

2. Travel Photography

When you’re traveling, you don’t usually want to bring a lot of lenses. Lighter gear means more room to pack other stuff for more convenient travel. So, most photographers choose a standard zoom lens or an extra telephoto travel lens.

If you’re going to a place with many landmarks or vast landscapes, I suggest you include at least a moderately wide lens. It might be enough if your kit lens goes as low as 24mm. (Remember that 18mm kit APS-C lenses are equivalent to 27mm on a full frame.)

I seldom bring a standard zoom lens when traveling. Instead, I rely on a wide-angle prime lens and a short telephoto prime.

My two favorite lenses for travel are the 24mm f/1.4 and the 85mm f/1.8. Sometimes, I throw in a 40mm f/2.8 pancake lens because of its tiny size. Learn more about travel photography in our Next Stop: Travel Photography eBook.

Shot with a Sony a7C and 28-60mm wide angle lens. 28mm, f/6.3, 1/400 s, ISO 800. Photo by Dibakar Roy (Unsplash)

3. Architecture and Real Estate Photography

For these specific purposes, you’ll need to have a wide lens. An ultra-wide lens is recommended for interiors. Aperture and build quality are not really of consideration here. What you need is a versatile, sharp, and wide lens.

You might opt for a tilt-shift. They give you excellent image quality, advanced controls, and distortion-free results.

Canon and Nikon both make fantastic tilt shifts, often for astronomic prices. Samyang, a third-party manufacturer, offers less expensive options that still give you lots of value. Check out our Picture Perfect Properties eBook to learn about real estate photography.

Shot with a Nikon D850 and an ultra-wide angle lens. 14mm, f/7.1, 1/320 s, ISO 200. Photo by Justin Wolff (Unsplash)

4. Landscape Photography

For landscapes, you inevitably need a wide-angle lens. As you’ll probably do it from a tripod, the aperture is not a very important factor. Instead, size, weight, image quality, and weather sealing are.

The lens we love for landscapes is the Canon EF 16-35mm f/4. You can learn the ins and outs of landscape photography in our Simply Stunning Landscapes and Epic Landscapes Editing courses.

Shot with a Canon EOS 5D Mark IV. 15mm, f/10, 0.3 s, ISO 400. Photo by Dave (Unsplash)

5. Event Photography and Photojournalism

These fields require fast and wide lenses (among other gear). You have to be ready for numerous lighting and action situations.

Use wide-angle lenses when you need to capture the all-encompassing shot. You can also use them to get very close-ups for dramatic angles. Remember Capa’s words.

You have several options. You can choose a wide-zoom lens. Several 16-35mm f/2.8 lenses are very popular. Canon has a 16-35mm f/2.8 version, and Sony has one. Nikon makes a 14-24mm f/2.8, along with Sigma (also for Canon and Nikon).

These are all versatile, well-built lenses. And they provide adequate image quality. But they are all serious investments.

Sadly, with zooms, you very rarely get below f/2.8. It’s best to raise the ISO to capture moving subjects in low light, which results in more noise.

The way I prefer is going with wide aperture primes. I’m a big fan of a 24mm f/1.4 lens. But there are other options. Most brands make 35mm f/1.4 lenses. Tamron sells a 35mm f/1.4 (for Canon and Nikon), which I like a lot.

Sigma makes a 20mm f/1.4 lens if you need a wider lens. If you need even wider (rarely the case), there’s the 14mm f/1.8. It’s a unique lens, not challenged by anything else on the market, but not particularly suited for photojournalistic applications.

Shot with a Nikon D5500 and its 18-35mm kit lens. 32mm, f/10, 100 s, ISO 100. Photo by Abhyuday Majhi (Unsplash)

6. Night Sky Photography

If you want to photograph the night sky (maybe the Milky Way), fast prime lenses are the way to go, especially the Sigma 14mm f/1.8 lens for Canon, Nikon, or Sony.

Follow our guide in the Milky Way Mastery course to learn about this field and its use of wide-angle lenses.

Shot with a Nikon Z5. 17mm, f/2.8, 160 seconds, ISO 6400. Photo by Evgeni Tcherkasski (Unsplash)

Why Not Use Your Normal Lens?

You can use a multitude of lenses to try to replicate the view from wide-angle lenses. For example, if you can use a standard 50mm lens.

To get a 16 mm view, you would have to shoot a few dozen images and stitch them together with software. Six to eight images may be enough to cover 28mm.

You’ll need editing software such as Adobe Photoshop or Lightroom. If you have the time, the non-moving subject, and the effort required, you can succeed with it. Your combined image will also have a much higher resolution than a single shot.

Stitching also requires different considerations. You can use it to replicate the shallow depth-of-field look of large formats. And nothing stops you from doing it with portraits or product shots.

The pioneer of this technique is Ryan Brenizer, a wedding photographer from New York. He achieves impressive background separation and wide angles simultaneously with it.

Of course, other photographers also borrow his trick. Perfecting this takes time, particularly with portraits, but the results are rewarding.

Shot with a Canon EOS 6D. 35mm, f/3.5, 1/200 s, ISO 2000. Photo by Letícia Pelissari (Unsplash)

Conclusion: What Is a Wide Angle Lens?

Beginner photographers often neglect wide-angle lenses. But they are powerful tools of expression, providing options that no other lens type is capable of.

Wide-angle lenses can also pose challenges. Applying composition and exposure skills to wide-angle shots can be harder than expected.

It’s important you feel comfortable using your wide-angle glass without overthinking it. Going with your flow almost always yields great results. This way, your shots will be genuinely great and unique.

If you’re looking for a great wide angle, read our guides on choosing the best Canon, Nikon, or Sony wide-angle prime lenses. We also have articles on the best Canon, Nikon, or Sony wide-angle zoom lenses.

Our Top 3 Choices for the Best Wide-Angle Zoom Lens