Wildlife photography is one of the most rewarding genres, but it can be tricky if you don’t have the right wildlife photography gear.

You can use pretty much any camera and lens to snap pictures of creatures and critters in your backyard or local park. But if you want to get serious about shooting animals, you’ll need to invest in the best wildlife photography gear.

This article looks at all the best gear for wildlife photography. We start with cameras, but also we cover everything from lenses to camera backpacks.

Wildlife photography can be a tricky genre to get into. It’s incredibly fun and rewarding if you’re an animal lover, but getting the best results requires a lot of specialist gear. The financial burden is one of the main problems, of course. But even if you have the budget, finding exactly what you need to get the shots you want can be challenging.

This article is the perfect place to start if you’re looking for the best gear for wildlife photography. We tell you what you need and why you need it, and we provide examples of the best products available.

Each section has a link to a full article on the subject, so remember to click the links to learn more. You can also click the following link to see our full guide on how to take wildlife photos.

Before you head out into the wild, you need a camera that’s up to the job. It doesn’t have to be the most high-tech camera on the market, but you need one capable of snapping animals in their natural environments.

The Sony a9 II is our top pick thanks to its impressive 20 fps continuous shooting, lightning-fast autofocus, and 5-axis in-body image stabilization. It also has improved ergonomics and great file transfer speeds.

For those on a budget, the Pentax K-70 offers excellent low-light performance with a wide ISO range, built-in image stabilization, and a durable, weather-sealed body. The high-quality pentaprism viewfinder is another standout feature.

The Panasonic Lumix DC-G9 II is the best Micro Four Thirds option, with a High Resolution mode for detailed images, 4K/60p video, and a rugged design. The custom buttons, top LCD screen, and Wi-Fi/Bluetooth connectivity add to its appeal.

To learn more about the best camera for wildlife photography, check out our in-depth guide.

The best underwater cameras are compact, easy to use, and of course, waterproof. Our top pick is the Olympus Tough TG-6 for its rugged design and excellent image and video quality. It’s waterproof down to 49 ft (15 m), shockproof, and crushproof.

The GoPro Hero11 Black is another great option, especially for capturing underwater video. It shoots 5.3K video and 27 MP photos, and is waterproof to 33 ft (10 m). The HyperSmooth 5.0 stabilization ensures smooth footage.

For serious divers, the SeaLife Micro 3.0 is a top choice. It’s waterproof to an impressive 200 ft (60 m) and has underwater color correction and manual white balance settings. This compact camera captures 16 MP stills and 4K video.

Underwater cameras are essential for capturing the beauty beneath the waves. With the right camera, you can document your underwater adventures and the amazing marine life you encounter.

Finding the right lens is half the battle when it comes to wildlife photography. In most instances, a 50mm prime isn’t going to get you amazing wildlife photos. You won’t be able to get close enough to the animals to actually take a picture.

That’s why telephoto lenses are essential for serious wildlife photographers. They give you the magnification you need to get close-up shots without getting too close to the animals. This means you don’t scare the animals off or put yourself in danger.

Let’s take a close look at wildlife photography lenses so you can find exactly what you need for your next wildlife expedition.

A telephoto lens has a long focal length that makes distant objects appear closer. They are great for shooting subjects you can’t get close to, like wildlife or sports. Telephoto lenses also create a shallow depth of field, which blurs the background and makes the subject stand out.

Telephoto lenses come in different focal lengths. Short telephotos (85-135mm) are good for portraits and events. Medium telephotos (135-300mm) offer more reach at an affordable price. Super-telephotos (over 300mm) are used by pros for sports, wildlife, and astrophotography.

Using a telephoto lens on a crop sensor camera makes the subject appear even closer. This is because the smaller sensor crops the image, effectively increasing the focal length. If you want to learn more about telephoto lenses, check out our in-depth guide.

The best lenses for wildlife photography offer powerful magnification. They allow you to capture animals in their natural habitat without getting too close.

A large focal length range is important. Telephoto lenses between 400 and 600mm are popular for wildlife photography. They give you the reach to photograph distant animals. Zoom lenses are also very useful. They let you quickly adjust the composition without changing lenses.

Look for lenses with fast autofocus and image stabilization. These features help you capture sharp photos of moving animals. The Sigma 150-600mm f/5-6.3 DG OS HSM is a great option. It has a huge zoom range and is one of the best lenses for wildlife photography.

When choosing the best Canon lenses for wildlife photography, consider focal length, aperture, and image stabilization. Our top pick is the Canon RF 600mm f/11 IS STM. It’s lightweight and has 5-stop image stabilization for sharp shots.

The Canon RF 600mm f/4L IS USM is a pro-level option with a bright f/4 aperture and weather sealing. For extreme reach, the Canon RF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM delivers exceptional clarity and fast autofocus.

Budget-conscious photographers may like the Tokina SZ Pro 300mm f/7.1 Reflex MF CF. It’s affordable and compact, but it lacks autofocus. But whatever your needs, there are lots of Canon lenses available for capturing stunning animal images.

Finding a budget Canon telephoto lens might sound difficult, but there are some great options available. The Canon RF-S 55-210mm f/5-7.1 IS STM is a top pick for Canon’s entry-level APS-C mirrorless cameras. It offers an impressive zoom range, near-silent STM autofocus, and up to 4.5 stops of image stabilization in a compact, lightweight design.

The Canon EF 70-300mm f/4-5.6 IS II USM is an excellent choice For Canon EF-mount cameras. This lens delivers superb image quality, fast and accurate autofocus, and built-in image stabilization at a reasonable price point.

If you’re looking for an affordable way to capture distant subjects, consider the Tokina AT-X AF SD 400mm f/5.6 for Canon EF. This compact and lightweight lens offers impressive build quality and value for a super-telephoto focal length. To learn more about budget Canon telephoto lenses, check out our in-depth article.

Nikon offers a wide range of lenses perfect for wildlife photography. The Nikon Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 VR S is our top pick, delivering sharp images and effective stabilization in a lightweight design. Its broad zoom range provides the versatility needed to capture animals both near and far.

For those using Nikon DSLRs, the AF-S 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR is a popular choice. This lens maintains a constant f/5.6 aperture throughout its zoom range, allowing for consistent exposure. The ED glass elements minimize chromatic aberration, ensuring clear and detailed images.

Both lenses feature weather sealing, making them suitable for outdoor use in various conditions. They also have fast, quiet autofocus systems that help you quickly lock onto your subject without startling them.

Nikon lenses for wildlife photography provide the reach, image quality, and durability needed to capture stunning shots of animals in their natural habitats.

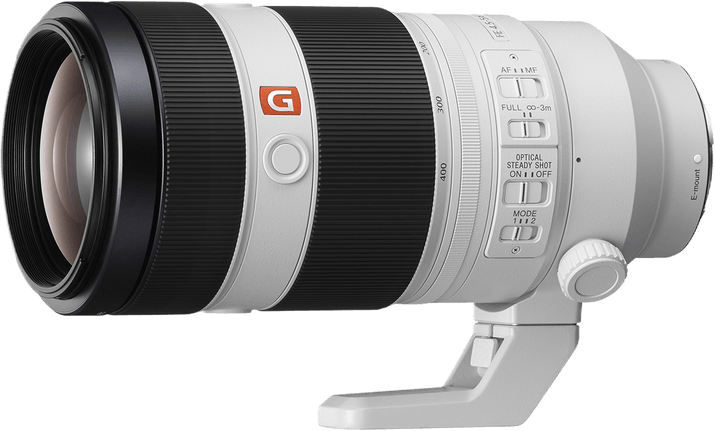

Sony offers a range of lenses perfect for wildlife photography. The Sony FE 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 GM OSS is a great choice, with its versatile zoom range and effective image stabilization. It delivers sharp images across the focal range and has a durable, weather-sealed build for outdoor use.

For APS-C shooters, the Sony E 70-350mm f/4.5-6.3 G OSS is ideal. This lightweight lens has a versatile zoom range, fast autofocus, and built-in stabilization for capturing sharp wildlife images.

The Sony FE 200-600mm f/5.6-6.3 G OSS is the best super-telephoto zoom, with its long focal range for distant subjects. It offers sharp imagery, fast autofocus, and effective stabilization in a durable design.

Sony lenses for wildlife photography help you capture stunning animal images in various outdoor conditions.

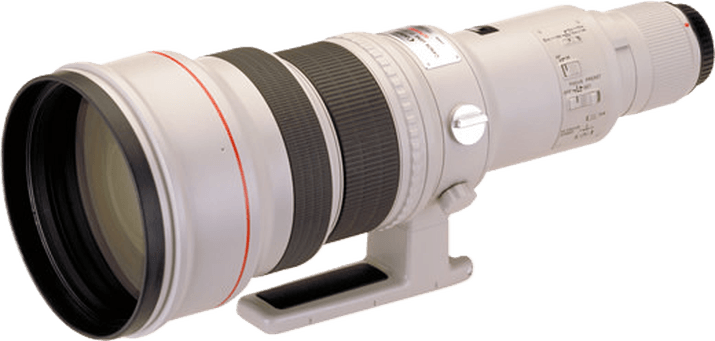

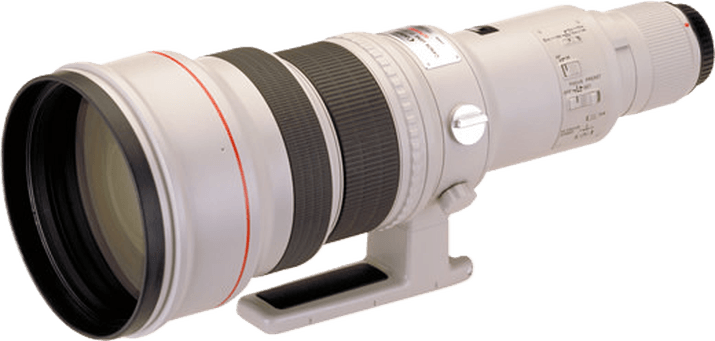

Super-telephoto lenses are a must-have for wildlife photographers. They allow you to capture close-up shots of animals from a distance.

The Tamron SP 150-600mm f/5-6.3 Di VC USD G2 is a great option that performs well at an affordable price. This lens has a wide zoom range, making it versatile for different styles of photography. It also produces sharp, contrast-heavy images.

The Sigma 500mm f/4 DG OS HSM is another top choice, especially if you prefer prime lenses. It offers superfast autofocus and a wide maximum aperture.

When choosing a super-telephoto lens, consider the focal length, max aperture, image quality, and autofocus speed.

Super-telephoto lenses can be expensive, so you may need to compromise on certain features to find one that fits your budget.

The best 150-600mm lenses offer incredible magnification and versatility. They deliver sharp images throughout the zoom range. Fast autofocus and image stabilization are also important features.

Sigma’s 150-600mm f/5-6.3 Contemporary DG OS HSM is a top choice. It has strong optical quality and a quick, responsive autofocus system. The built-in optical stabilization helps when using slower shutter speeds or panning.

This lens is available for Canon, Nikon, and Sigma cameras. It’s also one of the best-value super-telephoto zoom lenses on the market. 150-600mm lenses like this Sigma are very useful for sports and wildlife photographers who need powerful magnification.

The best lens for bird photography helps you capture stunning images of your feathered subjects. A focal length of 400-600mm is ideal, providing enough reach to photograph birds from a distance. Look for lenses with fast autofocus and reliable image stabilization to ensure sharp shots.

Professional bird photographers often use large, heavy lenses like 500mm and 600mm primes. However, these aren’t always practical, especially when traveling to remote locations. Smaller, lighter options like the Olympus 300mm f/4 PRO with a 1.4x teleconverter can provide an 840mm equivalent focal length in a compact package.

Ultimately, the best lens for bird photography depends on your specific needs and shooting situation. With advancements in technology, even affordable lenses can deliver professional-quality results. Choose a lens that balances focal length, image quality, and portability to help you capture stunning bird images.

Our top pick is the Canon RF 600mm f/11 IS STM for its impressive reach and portability. This lens captures distant subjects clearly, making it ideal for bird photography.

Other great options include the Canon RF 600mm f/4L IS USM for low-light performance, and the Canon RF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM for even greater reach. The Sigma 200-500mm f/2.8 APO EX DG for Canon EF is a versatile zoom lens with a fast f/2.8 aperture, perfect for shooting with a fast shutter speed.

No matter which lens you choose, these Canon lenses will help you capture stunning images of birds in their natural habitats. Canon lenses for bird photography offer a range of focal lengths and features to suit your needs and budget.

Nikon offers a range of lenses perfect for bird photography. The Nikon Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 VR S and Nikon AF-S 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR are two of the best.

The Nikon Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 VR S has a versatile zoom range, letting you frame birds up close or in the distance. It’s sharp, has fast autofocus, and offers 5.5 stops of image stabilization.

The Nikon AF-S 500mm f/5.6E PF ED VR is a lightweight prime lens with a 500mm focal length. This makes it easy to carry on long shoots. The lens is very sharp and has fast, accurate autofocus to capture birds in flight.

Nikon lenses for bird photography come in many focal lengths and apertures. Finding the right one will help you take your bird photography to new heights.

The Sony FE 400mm f/2.8 GM OSS and FE 600mm f/4 GM OSS offer exceptional reach and low-light performance, perfect for capturing detailed shots of birds from a distance. The FE 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6 G OSS is a versatile zoom lens that allows you to quickly adapt to different shooting situations.

Other great options include the Sigma 150-600mm f/5-6.3 DG DN OS | S and the Tamron 150-500mm f/5-6.7 Di III VC VXD, both of which provide an extensive zoom range and effective stabilization for sharp images. For those seeking a lightweight and compact option, the Tamron 70-300mm f/4.5-6.3 Di III RXD is a great choice.

No matter which lens you choose, you’ll be able to capture stunning images of birds in their natural habitats. Sony lenses for bird photography offer a range of features to help you get the perfect shot.

The right accessories can be a huge help for wildlife photography, especially out in the field. But you also want to minimize the amount of gear you need to carry, so we’ve compiled a list of accessories worth taking with you.

A sturdy tripod is a must-have for wildlife photographers. It’s especially useful when shooting in low light with slow shutter speeds. Even the slightest camera movement can cause blurriness.

Filters protect your lens and help you get better images in difficult lighting. UV filters block unwanted UV light and reduce haziness. Polarizing filters add contrast, reduce reflections, and darken skies. And neutral density filters prevent overexposure in bright light.

A rain cover will protect your camera from rain and snow. It’s important to keep your gear safe from the elements. Filters for wildlife photography are very useful accessories that can greatly improve your images.

Here’s our in-depth article on the best accessories for wildlife photography.

A teleconverter is a camera accessory that extends the focal length of your lens. It sits between the camera body and lens, increasing the distance between the focal point and the camera sensor. This gives your lens a longer reach, allowing you to capture distant subjects with ease.

Teleconverters come in different levels of magnification, such as 1.4x and 2x. A 1.4x teleconverter used with a 300mm lens increases the focal length to 420mm, while a 2x teleconverter doubles the focal length. They’re popular among wildlife, sports, and astrophotographers who need extra reach without getting too close to their subjects.

Using a teleconverter is simple—just attach it to your camera like a regular lens, then attach your lens to the teleconverter. Keep in mind that teleconverters can affect image quality and reduce the maximum aperture of your lens. To learn more about teleconverters and how they can improve your photography, check out our in-depth guide.

Teleconverters are a great way to get more reach from your lenses. They sit between the camera body and lens, increasing the focal length. This extra magnification is perfect for wildlife, sports, and landscape photographers who need to capture distant subjects.

The best teleconverters have excellent glass elements that maintain image quality. They’re also durable and can handle tough outdoor conditions. But teleconverters do have some downsides, like reduced aperture ranges and slower autofocus speeds.

If you’re looking for a top-quality teleconverter, consider a teleconverter from Canon, Nikon, Sony, and Sigma. These brands offer 1.4x and 2x extenders that are compatible with many of their telephoto lenses.

With the right teleconverter, you can get the extra reach you need without spending a fortune on a new lens.

A tripod is an important tool for many photographers. It keeps your camera steady in low light and when using slow shutter speeds. Tripods come in different sizes and materials like aluminum or carbon fiber.

The best tripod for you depends on the type of photography you do. Landscape photographers need a sturdy tripod to shoot in windy conditions and with heavy cameras. Travel photographers want a lightweight and compact tripod that’s easy to carry.

Look for a tripod that extends to your eye level and can hold the weight of your camera. Quick-release plates make it fast to attach and remove your camera. And adjustable legs help you shoot on uneven ground.

If you want to learn more about tripods, read our full guide on how to choose the best tripod for you.

A camera bean bag is a simple yet effective tool for stabilizing your camera, especially when shooting wildlife or nature photos. It molds to your lens and the surface you place it on, providing flexible support without getting in the way.

Bean bags are great for photographing from your car. You can use them to steady your camera on the door frame or window, allowing you to get closer to wildlife without scaring them away. They also come in handy when tripods aren’t allowed or when you need to get a low-perspective shot.

You can easily make your own bean bag using soft, durable fabric and a filling like rice, beans, or plastic beads. Choose a size that fits your needs, whether it’s a small bag you can toss in your camera bag or a larger one for added stability.

Check out our in-depth article to learn more about camera bean bags.

The Vortex Optics Viper HD is among the best binoculars for wildlife photography. These binoculars have 10x magnification and 42mm objective lenses, providing a clear and detailed view. The HD Extra-low Dispersion glass ensures high resolution and color accuracy.

The Viper HD binoculars are built to last with a rubber-armored chassis and ArmorTek coating. They are also argon-purged and O-ring sealed for waterproof and fogproof performance, making them suitable for all weather conditions.

With a close focusing distance of 5.1 ft (1.6 m), these binoculars allow you to observe wildlife in great detail. If you want to learn more about binoculars for wildlife, check out our article to help you choose the right pair for your needs.

A spotting scope is an essential tool for bird photographers. It allows you to see birds clearly from great distances, helping you identify species and align your shots.

When choosing a spotting scope, consider the magnification range, objective lens diameter, and field of view. Look for a scope with high-quality glass and coatings to reduce aberrations and improve light transmission. Durability is also important, so choose a waterproof and fog-resistant model.

A spotting scope for birding can come in many shapes and sizes. You can find scopes with long magnification ranges, high-end optics, and modern features like smartphone integration. There are also budget-friendly options that still provide excellent performance.

Every photographer needs a good camera backpack. And that’s especially true for wildlife photographers. They need a spacious backpack capable of carrying large lenses that also provides protection. Telephoto lenses are not cheap, so you need security when stowing them in your backpack.

Thankfully, we’ve reviewed several camera backpacks that fit the bill. We also have a full article on waterproof backpacks for photographers heading out in bad weather.

The Gura Gear Kiboko V2.0 22L is a tough camera backpack made for wildlife photographers. It has a rugged, weather-sealed design that makes it great for outdoor adventures.

You can fit a lot of camera gear in this 22-liter bag. The space is used well, so you can pack large telephoto lenses and several camera bodies. The shoulder straps, chest strap, and waist belt are all very comfortable, even when carrying heavy loads.

This high-quality backpack comes at a high price. But if you want a reliable bag that will last, it’s worth the investment. Gura Gear also offers a five-year warranty for extra peace of mind.

Check out our full-length review to learn more about the Gura Gear Kiboko V2.0.

The Think Tank MindShift BackLight 18L is a hiking-style camera backpack. It has an impressive carrying capacity for its size. You can fit two full-frame DSLRs, two zoom lenses, a flash, and accessories.

The backpack is well-made but has less padding than some alternatives. This helps keep the weight down, which is important for long hikes. And there are many ways to attach extra gear to the outside of the bag.

The MindShift BackLight 18L is a good choice if you want a light yet spacious camera backpack. Check out our full-length review to learn more about the Think Tank Mindshift Backlight 18L.

Protecting your expensive camera gear from the elements is crucial. The best weatherproof camera bags use special materials and coatings to keep your equipment dry, even in sudden downpours.

Our top picks feature incredible exterior materials that don’t need a cover if it starts to rain. The Wandrd Prvke has a roll-top design that keeps water out, while the Wandrd Duo and Lowepro Freeline use waterproof zippers to secure even the weakest points.

When choosing a weatherproof camera bag, consider how it functions for your photography style. Look for different access options, additional features, and the level of weatherproofing that’s important to you.