At some point in the last 10 years, there has been a seismic shift in the mirrorless vs DSLR debate. The tide has turned, and now the mirrorless camera is rising in popularity and demand.

When I switched to professional photography, I asked my lifelong friend and pro Stuart Boreham what he thought of mirrorless cameras. His brief reply was, “I don’t.”

Well, things have changed, and you might wonder what the best way forward for your gear is. Should it be mirrorless or DSLR? We’ve compiled this guide to show the differences and remove the stress.

We examine the history of the two camera formats and the pros and cons of each. We think the future is mirrorless, but the answer might still be a DSLR for some people. After reading our article, you’ll know which is right for you.

A Digital Single Lens Reflex (DSLR) camera is the direct, digital descendant of the Single Lens Reflex camera (SLR). And those are called “Single” lens reflex because they followed the Twin Lens Reflex camera, most famously made by Rollei.

Photo by Umberto (Unsplash)

When you use a TLR, you look down into the viewfinder. The top lens projects an image via a mirror (hence “reflex”) onto a ground glass screen. The bottom lens then captures the image on the film.

The advantage of the TLR is that you can look at the viewfinder rather than through it, which helps with composition. The film also gives a 2-1/4-inch (6 cm) square image.

The disadvantages are many. The image in the viewfinder is reversed, so you have to learn to pan left when you want to move right. They also don’t work well in bright sunlight.

Plus, to focus accurately, you might need to flip out the magnifier to check that everything is correct. And parallax errors creep in as you get closer to your subject.

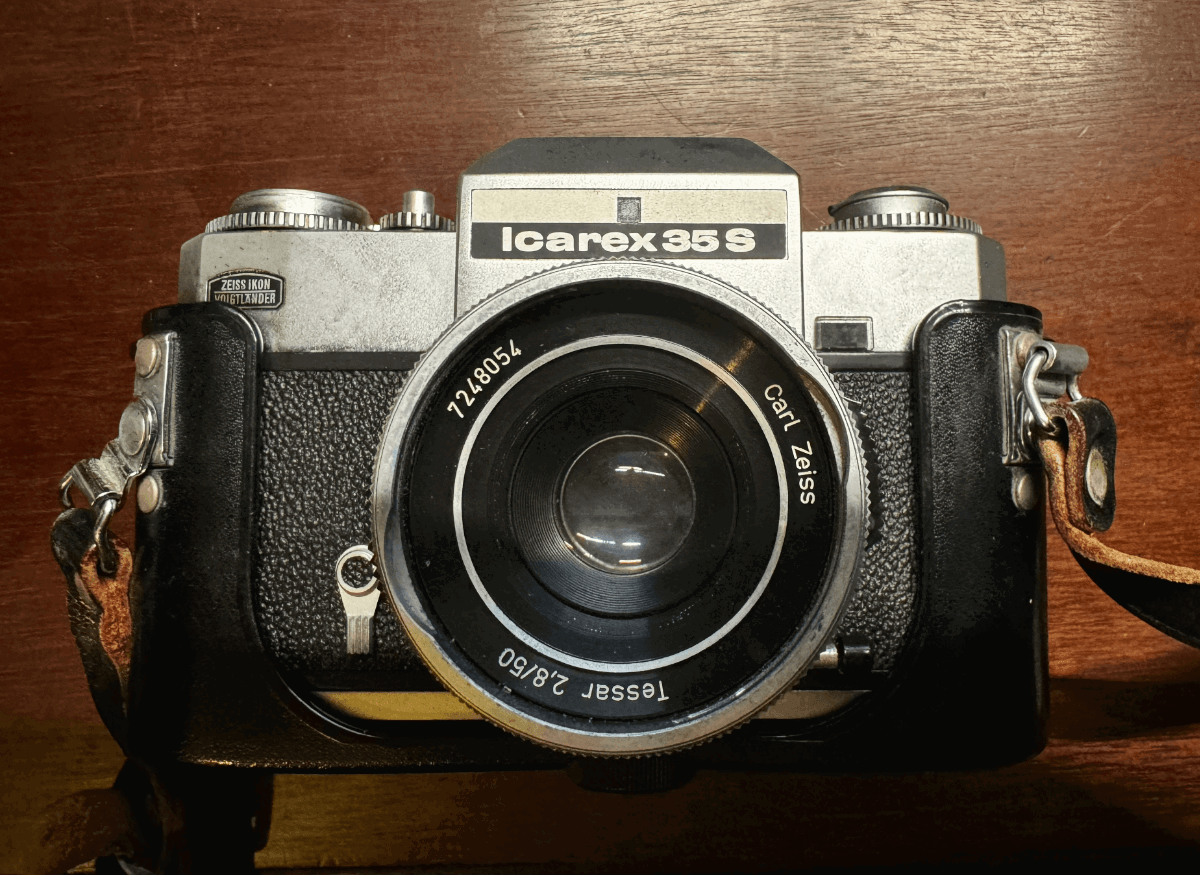

A Vintage Zeiss Ikon Voigtlander Icarex 35S SLR

These problems were eliminated over time by the development of the SLR. It’s a combination of some pretty amazing engineering and technology. But if you want to use one lens for viewing and shooting, you need some clever solutions.

Two things are essential for an SLR to work. A moveable mirror that swings up out of the way when the shutter fires and a pentaprism.

The mirror, angled at 45 degrees, sends the image to a ground glass focusing screen and then to the viewfinder. When the shutter is pressed, it rapidly swings up and out of the way, letting light reach the film. It then returns to the starting position.

The pentaprism bounces the image from the focusing screen off two surfaces and directs it to the viewfinder. That process sends the light in the same direction it originally traveled. It corrects the image reversal so the viewfinder sees the scene as it is.

It’s a slick operation. Take the flagship Canon EOS 1-V, their last great SLR. It could shoot at 10 frames per second (fps). That’s the same speed as your blink reflex.

In that incredibly short time, it flips up the mirror, opens and closes two shutter curtains, and closes the iris to the required aperture. Then, it returns the mirror to the starting place, opens the aperture, and winds the film onto the next frame. Incredible!

The first shutter curtain on an SLR, moving right to left to start the exposure.

The current Canon DSLR flagship, the EOS 1D X Mark III, shoots at 16 fps. That’s partly because it doesn’t have to wind the film.

For a DSLR, this is the limit of what is physically and mechanically possible. You can lock up the mirror and shoot at 20 fps in Live View mode, but that’s your limit.

But then innovations came along. The arrival of Through The Lens (TTL) metering meant you could set the exposure while looking through the viewfinder. At first, you had to stop the lens down to do this, making the image dark in certain circumstances.

Eventually, it became possible to overcome that. Autofocus came along, and fancy innovations like semi-silvered mirrors allowed metering and focus. My last Canon SLR even had eye-controlled focus.

It then became possible to make camera sensors of high enough quality to be used in expensive cameras. That meant the Digital SLR arrived, and the age of the DSLR was born!

It’s worth noting that the first Canon pro-level DSLR, the EOS 1D, had a 4.15 MP sensor. That’s laughable in today’s terms. But, the revolution had happened. The DSLR gradually replaced the SLR in every area of use.

There were many advantages to digital. You could take many more photos than the 36 allowed by 135 film. (There was a curious bulk film back available for some pro SLRs that gave up to 750 shots on a 100-meter roll of bulk film. But that was an exception.)

With digital, you can see the result immediately and adjust accordingly. Eventually, DSLRs outgunned SLRs in every aspect. But it was a while before they impacted the professional market.

This Nikon MF-24 film back allowed the F4 to take up to 250 shots.

Besides (D)SLRs, almost every camera is “mirrorless.” So, describing one particular camera style as mirrorless is a little odd. But it’s shorthand for an interchangeable-lens camera that relies on electronics to show the user what is being framed in the shot.

Sony blazed the trail with their Alpha 7R in 2013. But it was five more years until the heavyweights of pro photography, Canon and Nikon, followed suit. In the following five years, the mirrorless camera was not just a viable competitor but increasingly a superior beast.

We will now compare the camera features of DSLR vs mirrorless.

There are two main approaches to letting the user see the framed image. Pretty much every mirrorless camera has a screen for viewing the images. And some have an electronic viewfinder (EVF) as well.

An EVF is a small screen you look at through an SLR-style viewfinder. There are advantages over what you get with a DSLR. For one thing, you can see the real-time effects whenever you adjust your exposure.

There are other advantages. Modern camera sensors are amazingly sensitive in low light. This means you can see things with an EVF that are near-invisible through a DSLR viewfinder.

There are some shortcomings, though. Because it is a screen, there is some lag in the image. As technology improves, this becomes less of an issue. And it’s most noticeable when the camera, subject, or both move quickly.

The best mirrorless cameras reduce these issues to a negligible minimum. But it’s something to consider when comparing the two types of cameras. One reason for using the EVF has little to do with how we see things.

The traditional photographer’s stance is undoubtedly second only to a tripod for stability. Elbows in, one hand under the camera, and face pressed to the camera as you look through the viewfinder. It’s impossible to achieve with a viewfinder-less camera.

On the other hand, the EVF adds bulk. One advantage of the mirrorless camera is that it can be more compact than its DSLR cousin. As with all things concerning camera gear, it’s a tradeoff of features. We all have to decide the balance for our needs, wants, and budget.

DSLRs and mirrorless cameras benefit from a color screen for viewing.

There are some areas where mirrorless cameras have left the DSLR way behind. One is in drive speed, called “burst rate,” measured in frames per second (fps). This “frames per second” measures how many shots a camera can take per second in burst mode.

As we saw earlier, the shutter in a DSLR performs many very fast, precise mechanical actions. But there are limits. You can make a mirror mechanism faster by making it lighter. But at some point, you reach the physical limits.

A mirrorless camera only has to focus on the shutter itself. Most high-end mirrorless cameras offer both a mechanical and an electronic shutter.

The former is likely a focal-plane shutter. Two “curtains” move across the aperture at the back of the camera in front of the sensor. The gap left between these two curtains determines the shutter speed. This feature is a leftover from SLRs.

The focal plane shutter is fast and reliable. But it has the disadvantage of limiting flash sync speed. And in most cases, the fastest shutter speed you get is 1/8000 s (seconds). But it’s fair to say that’s pretty fast.

DSLRs that offer a Live View mode also use an electronic shutter. The mirror is locked up, and the image falls constantly on the sensor. The mechanical shutter usually plays a role in the final exposure.

Mirrorless cameras can also offer an electronic shutter. Now, this isn’t a shutter as such. It describes turning on the individual pixels for the required exposure. This has the advantage of allowing faster shutter speeds and faster drive speeds.

At the beginning of 2026, Sony caused a little stir by announcing that their Alpha 9 Mark III would feature a “global” shutter—a first for a full-frame camera. Simply put, a global shutter exposes every pixel at the same time.

Sony a9 III mirrorless camera

Conventional electronic shutters expose a band of pixels at a time. This is because the data needs to be processed. Of course, the more data there is, the more processing power you need.

Sony has produced a processor that can handle this high demand, resulting in an astonishing 120 fps drive speed. Another advantage of a global shutter is that it almost eliminates the rolling shutter effect.

It also offers absurdly fast flash sync speeds. And in the Sony, you get a maximum shutter speed of 1/80,000 s. For comparison, that’s about twice as fast as a lightning flash!

This is probably at the heart of why the DSLR is no longer the gold standard in photography. A DSLR cannot compete with a camera that can shoot 120 fps with focus tracking turned on.

One main advantage of mirrorless cameras over DSLRs is the autofocus. Autofocus systems have come a long way over the years. Modern systems can now detect eyes, distinguish between humans and animals, and track them as they move.

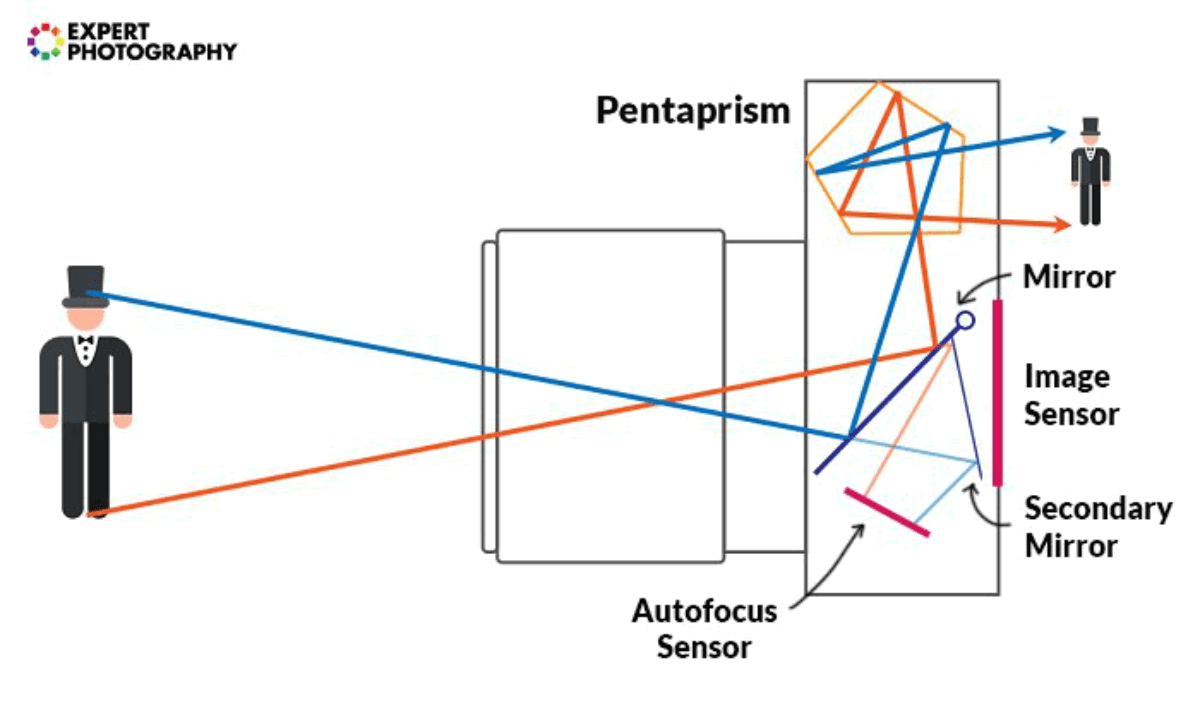

Mirrorless cameras have a distinct advantage in this. A DSLR AF system typically uses a semi-silvered mirror. This lets some light pass to the focus screen and some to the AF sensor. This is a decent solution, but it limits the coverage of the AF to a degree.

A mirrorless camera does not need a mirror, which means the AF functions happen on the sensor itself. Thus, the AF coverage can be across the whole sensor. It also has access to all the light passing through the lens.

This also means you’re more likely to find phase detection or hybrid AF systems on a mirrorless camera. This increases the speed and accuracy of the process.

A DSLR can’t compete with the compact size of some mirrorless rivals. Photo by Michael Soledad (Unsplash)

Once a clear dividing line between the two types of cameras, mirrorless cameras now have sensors at least as good as their DSLR counterparts.

For example, the top-of-the-range Canons (the EOS-1D X Mark III and the EOS R3) share the same DIGIC X processor. But the mirrorless R3 has a bigger and better sensor than the DSLR EOS-1D X.

The R3 is backlit with Dual Pixel AF capability. It outguns the DSLR in AF zones, speed, and control. Eye-control focus means that the camera focuses where you look.

Again, it used to be the case that if you wanted pro-level build quality and weather sealing, you had to get a DSLR. But now, you will find that mirrorless cameras match DSLR specs at every level.

If you find a DSLR too big and bulky, a mirrorless can win you over. Using the Canon examples above, the R3 body is nearly a full pound (450 g) lighter than the DSLR. And if you want to choose a mirrorless camera without EVF, then the difference will be even greater.

Smart money should be spent on mirrorless cameras, which means manufacturers’ R&D investments. DSLR production is stagnant at best and now a tale of discontinued models.

All the innovations come in the mirrorless camera world. It’s easy to see how the format will continue to outstrip what we thought was possible.

Expect to see the major manufacturers consolidate their mirrorless ranges and push their capabilities with ever-more eye-watering functionality. Eye-control focus, global shutters, pre-release image capture, and 6K video will likely become more commonplace.

I discovered that my friend Stuart (the one mentioned at the beginning of the article who scoffed at mirrorless cameras) bought a professional Canon mirrorless camera. This shows just how far the future of photography is heading when it comes to DSLR vs mirrorless.

The arguments stack up more and more on the mirrorless side. If you’re looking for a cheap first “serious” camera, there’s much to say about finding a good used DSLR. This is especially true if it comes with lenses with which to play.

If you’re building a system from scratch, a mirrorless camera is a clear winner. Whether you’re a casual user, serious enthusiast, or pro, the future is mirrorless.