Photography bracketing can help you photograph high-contrast scenes. Other approaches, like filters, have more drawbacks than advantages for HDR creation. Bracketing is an easy way to overcome technical limitations and create natural-looking images.

What Is Photography Bracketing?

Bracketing means creating several photos of a single scene with different settings. You can later use these bracketed photos to create an HDR (high dynamic range) photo.

Exposure bracketing is when a photographer creates pictures with different exposure settings. The purpose of this is to cover more of the dynamic range.

Other bracketing techniques include white balance bracketing or focus bracketing. The former is not required if you shoot RAW.

The latter is a great technique for focus stacking that increases the depth of field. We’ll touch on this later in the article.

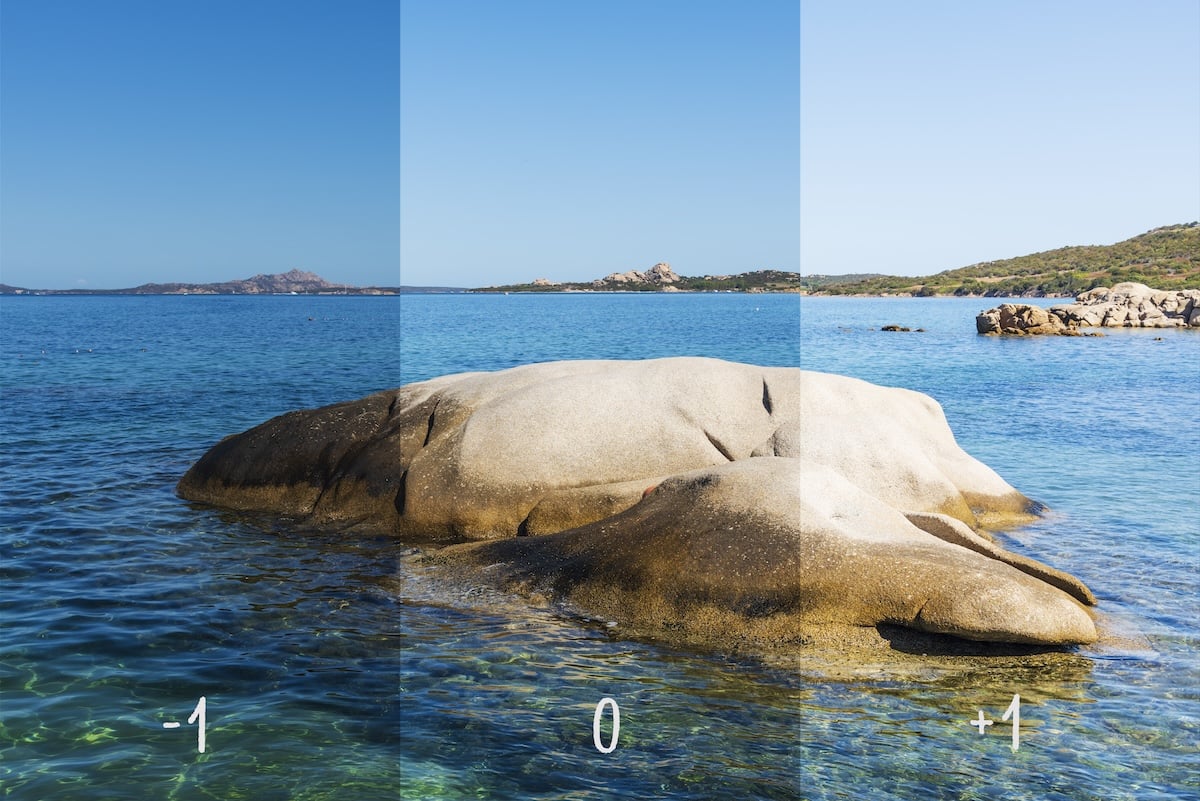

Three different exposure compensation shots of -1 EV, 0 EV, and +1 EV (iStock)

Why We Need Exposure Bracketing

The first issue a new landscape photographer has to overcome is this. A scene looks pretty. But a photo of that scene comes out with a white sky and black foreground.

Modern cameras are good at determining the right exposure compensation for each shot. But the technology isn’t as advanced as our eyes are. What the camera “sees” as the correct exposure value isn’t always right.

Our eyes quickly adjust when we look at a scene with high contrast. Our eyes’ “apertures” become wider or narrower fluidly. Cameras don’t work the same way. They have only one setting to capture a scene.

The exposure bracketing technique helps us overcome this limitation. It lets us capture the same scene multiple times with different settings to blend later.

When some people hear the term “HDR photo,” they freak out because the term has been abused and overused. An HDR photo done right looks natural and pleasing to the eye, which is when we need exposure bracketing.

I took the interior images below with three exposure compensation values (0 EV, -2 EV, and +2 EV). I then blended them in Photoshop to create a high-dynamic-range image.

How to Bracket Photos for HDR

First, an essential tool for any bracketing is a tripod. Sometimes, you can get away with handheld shots, but it’s risky and can result in disappointment. Here is a general plan to best bracket photos:

- Set your camera on a tripod.

- Select a bracketing mode in your camera settings. Refer to the camera’s user manual if you need help locating this.

- Select an appropriate number of brackets for the scene.

- Set the camera on a two-second delayed shutter. If you set the timer, the camera automatically takes all the brackets. You don’t have to click the button many times. This prevents the slightest camera movement and makes the blending easier.

- Click the shutter button.

If it’s windy and you have moving objects (like trees), raise your ISO. Then, you should set the camera to series mode rather than delayed shooting mode. You can then do the series by pressing the button longer.

Our Top 3 Tripods for HDR Bracketing Shots

EV (Exposure Value) Settings

There are two big questions here. How many brackets should there be? And how big of a distance should there be between brackets when it comes to exposure values (EVs)?

EV determines exposure compensation and is a term used for bracketing. Thus, (zero) 0 EV is the exposure your camera would pick automatically.

A -1 EV means its exposure is “minus one stop.” A +1 EV means its exposure is “plus one stop.” One stop equals double or half the amount of light the camera receives. So, -1 EV halves the amount of light, and +1 EV doubles it.

Modern cameras are advanced and have a high dynamic range. Because of this, I see no need to create brackets with just one stop between them. There are three types of bracketing settings that I use:

- 0 EV, -2 EV for most scenes

- 0 EV, +2 EV, -2 EV for real estate interiors and other high-contrast scenes

- 0 EV, +2 EV, -2 EV, +4 EV, -4 EV for rare cases when something is very contrasty. For instance, when the Sun is in the frame along with some dark cliffs.

You can have three stops between the brackets, but it makes it harder to blend. If you need three stops, it may be a better choice to do three brackets instead.

Merging Bracketed Images for HDR Photos

Many software applications let us merge bracketed images into a single HDR. They all have their pros and cons. It comes down to personal preferences and what works well for your workflow.

Adobe Software

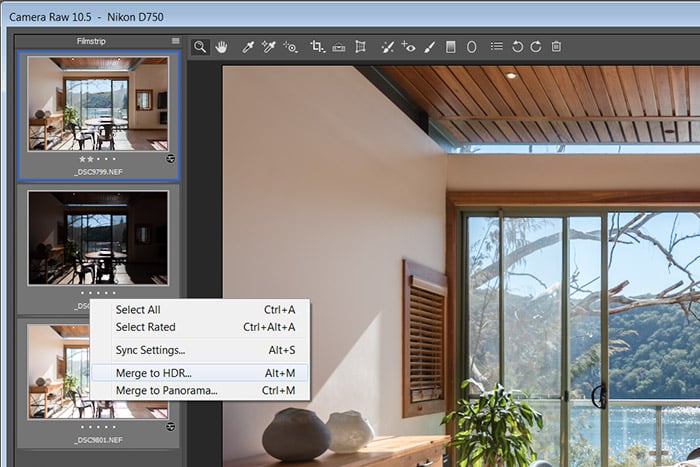

The most common editing tools photographers use are Lightroom and Photoshop. Both Adobe software can merge frames into a single picture. To do so, select the brackets, right-click, and choose Merge to HDR. Wait a little, and that’s it!

There are a few important things to know. Your photos may have moving objects, like trees or waves, making merging harder.

In this case, try the de-ghosting option these tools provide. The program will think a little more and try eliminating all object movements.

Set the amount of de-ghosting depending on the scene. Typically, low or medium work well enough. To check, zoom in on the part with the moving objects and see if it has any artifacts. More often than not, it does a satisfactory job of merging and de-ghosting.

I use Photoshop with built-in ACR (Adobe Camera Raw) for all my editing, including HDR merging.

Adobe Photoshop for JPEGs

If you are editing JPEG files and not RAW files, you still have the option to use Photoshop. There are three simple steps:

- Put all frames into the layers

- Select all layers to merge

- Edit > Auto-Align images (to get rid of any camera movements between the frames)

- Edit > Auto-Blend images

- Select Stack Images and press OK

Adobe Software for HDR Bracketing Merge

Photomatix, Aurora HDR, Enfuse

There are many applications, and covering them all here makes no sense. I’ll list the most popular ones. These are Photomatix, Aurora HDR, and Enfuse.

Photomatix is the app responsible for HDR’s bad rep. People have overused it so much that it’s common to think Photomatix is bad and amateurish. That is wrong.

A photographer should use it carefully and do as little HDR tone mapping as possible. Moderation is key. Otherwise, the colors start looking like nuclear pollution waste.

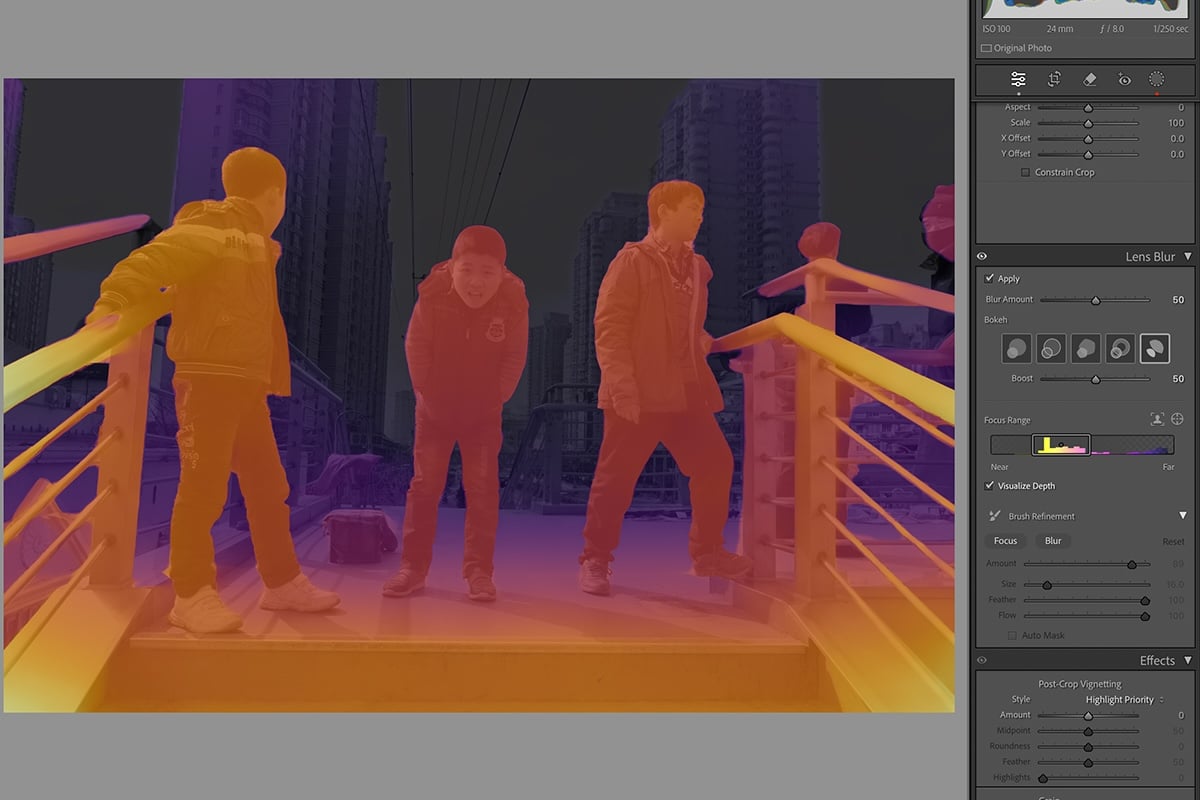

Aurora HDR is a great app with many tools similar to ACR and Lightroom. It does a good job merging the photos, and I got similar results. It may work slightly better than Adobe programs. But the difference is not big enough for me to change the workflow.

Enfuse is a Lightroom plugin that uses a few different algorithms to merge the photos in Lightroom. I’ve seen people achieving great results with it. But again, it complicates the workflow.

Manual Merge With Luminosity Masks

You can create HDRs by manually merging using luminosity masks. It’s the most advanced Photoshop technique. And it’s not easy to master. The general idea is to generate masks using the luminosity values of the image.

You can apply the changes only to the lights or the darks of the image. The drawbacks are the long editing time and the learning curve.

Single Exposure HDR

Modern cameras have quite a large dynamic range. Sometimes, you don’t even need two brackets to edit a photo. You can use a single shot and convert it twice with different settings.

For instance, maybe you have an image with very high contrast. You open it in a RAW converter, edit it for the darks, and open it in Photoshop. Then, open the RAW file again, edit it for the lights, and open it again.

This way, you now have bright and dark images in Photoshop. You can create an HDR using Photoshop merge or do it manually.

HDR photo shot with a Sony RX100 VII. 72mm, f/4.5, 1/200 s, ISO 1,250. Mihály Köles (Unsplash)

Focus Bracketing

Another type of bracketing is focus bracketing. Sometimes, the photo needs to have a wider depth of field than any aperture setting can provide.

In this case, we make brackets with different focus points and then blend them. Do the following to create bracketed images for focus stacking:

- Set your camera on a tripod

- Switch to manual focus

- Focus on the closest object and shoot (a remote helps prevent camera movements)

- Carefully rotate the focus ring to another object a few meters away. The focus should begin where the focus zone of the previous shot ends. Take another shot.

- Repeat until you cover all ranges up to infinity. Three shots with an f/16 aperture should be enough. Do more to be sure or if you need to set a wider aperture.

The takeaway is that you cannot bracket focus automatically with digital cameras. Changing the focus involves some manual labor.

Focus Stacking Images

Here’s how to blend focus stacking in Photoshop. The steps are very similar to the ones we had for the other Photoshop blend:

- Put all frames into the layers

- Select all layers to merge

- Edit > Auto-Align images (to eliminate any camera movements between the frames);

- Edit > Auto-Blend images

- Pick the Stack images mode, and it tries to blend it all automatically.

I found this algorithm less reliable than the HDR one. More often than not, it’s best to fix the masking manually (second image below) using a soft brush.

The alternative for this kind of merge is manual masking. You must Auto-Align frames still and carefully blend them with a soft brush with 10% opacity. Do it slowly, stroke by stroke, rather than one single hit with 100% opacity. This way, you achieve a seamless blend.

Conclusion: HDR Bracketing

Modern camera technology has advanced greatly, but it’s still imperfect. And I doubt it ever matches our eyes’ perception levels.

Different types of bracketing help us overcome these technical limitations. Use HDR blending instead of filters. And use focus stacking to get everything in focus, as it should be for landscape photography.